Barnsley war objectors faced white feathers and humiliation

I have learnt a lot about Quakers since I started helping out at the Maurice Dobson Museum in Darfield, where Geoffrey and Elsie Hutchinson (Barnsley Local Meeting of Quakers) are very actively involved. We have enjoyed many discussions about the First World War and my interest in conscientious objectors has expanded, especially since it is relevant to several old boys of Holgate Grammar School.On March 2, 1916 conscription was introduced for British men aged between 19 and 41 who were unmarried or widowed without dependent children. A list of exceptions included men who had come forward to enlist but been rejected and those discharged from service because of ill health, men in holy orders or regular ministers of any religious denomination and those with a certificate of exemption. Grounds for exemption included other work in the national interest, serious ill health or hardship or conscientious objection.Men could apply for a certificate from a tribunal.The Military Service Act made it a duty for men to die for their country and gave them the right not to fight but it would certainly not make it easy to refuse to take up arms.In August 1914, Vice Admiral Charles Cooper Penrose-Fitzgerald, who had retired from the Navy in 1901, had founded the Order of the White Feather with the support of author Mrs Humphrey Ward.The campaign spread and even included Suffragettes such as the PankhurstsThese women showed no discrimination about soldiers home on leave, men serving their country in other ways or those who had been discharged because they were wounded. They even presented a white feather to Seaman George Samson when he was wearing civilian clothes for a reception in his honour, having been awarded the Victoria Cross for gallantry.This led the Government to issue lapel badges reading ‘King and Country’ to employees in state industries and the introduction in September 1916 of the Silver War Badge for veterans honourably discharged.Conscientious objectors (COs) refused to fight on moral or religious grounds. During the First World War there were about 16,000, who showed great courage in standing up for their beliefs.The majority agreed to work on the land or in menial employment in hospitals or other institutions. Others joined the Royal Army Medical Corps as stretcher bearers, doing the dangerous work of rescuing wounded soldiers in battle.The Quakers established the Friends Ambulance Unit. They provided diverse medical support and staffed eight hospitals in France and Belgium.About 3,400 objectors were allowed to join the Non-Combatant Corps established in March 1916 as privates, who wore a uniform and were subjected to army discipline, undertaking labouring jobs. Those who refused to serve or were unwilling to wear the uniform or perform certain duties could be court martialled.About 6,000 men were imprisoned, often in inhumane conditions. Many suffered mental breakdowns and illness and some died as a result. The scandal created by the numbers involved led to work camp schemes. The conditions in the most notorious led to COs preferring to return to prison.Felicity Goodall’s We Will Not Go To War presents harrowing stories, while White Feather Diaries on the Quaker website provides more details.

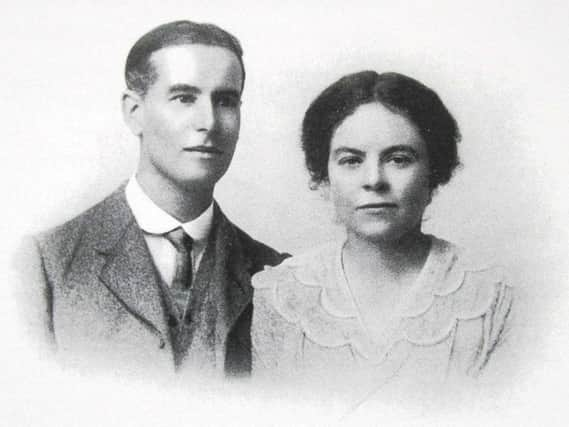

The Barnsley tribunals for conscientious objectors comprised Lieutenant Colonel Hewitt, the main interrogator, plus the mayor as chair and other aldermen. About 210 cases were reported on the front page of Barnsley Chronicle on March 4 and 25, 1916 and in between were reports on applications to the separate Colliery Court. Men were not named but would have been recognisable from descriptions printed.On March 25, the first six cases were considered. Most were refused but directed to the Non Combatant Corps. The first man was a linen drill warper at Taylor’s factory who explained that he had consecrated his life to God. Colonel Hewitt asked whether he would defend his mother if the Germans attacked her. His negative response elicited: “Then I submit this man has no conscience at all.” While one councillor objected to hypothetical questioning, another asked if the man had read any Shakespeare. “Well, read it and you will find Shakespeare says ‘Conscience doth make cowards of us all’. It looks so in your case.”A clothing manufacturer aged 33, who was a Congregationalist and had held for 15 to 18 years strong objections to anyone taking human life, was challenged whether a boy was capable of holding such views. He was allowed to join the Friends Ambulance Unit.It took courage for conscientious objectors to attend these tribunals, exposing themselves to mockery and censure. They also risked retaliatory attacks.* Thomas Corder Pettifor Catchpool helped set up the Friends Ambulance Unit in 1914 and worked with it in France, winning the Mons Star. When conscription was introduced in 1916, Corder felt that he could no longer serve in any capacity that would aid the war so he returned to England. He suffered repeated trials, court martials and imprisonment, damaging his health. After his release from prison in 1919, Corder worked with the Friends War Victims Relief Committee in Germany, having learnt German while in prison. He married Mary Gwendoline Southall in 1920 and they had four children.Esther Pleasaunce (Pleas) Catchpool shared her father’s convictions. She got married in 1954 to John Holtom, a mining engineer who rose rapidly in the industry in South Yorkshire, then the Energy Agency. John had been accepted into the Society of Friends after attending the Doncaster Meeting in the late 1940s.He met Pleas, who was on sabbatical as an art teacher at a London girls’ school, at a Quaker conference and she became an active member of the Barnsley Meeting. They had four children and lived in Wath for about 25 years.