Book Club: An art education through jigsaw puzzles and other stories in Italian

You, Bleeding Childhood is a collection of loosely connected stories about the days of Mari’s own childhood which he found crawling with monsters. At the crossroads of memory and myth, this book is Mari’s first attempt at cataloguing the cabinet of wonders of his youth. The young Mari, raised on comic books and science fiction, constructed an alternate universe for himself untouched by uncomprehending grownups or sadistic peers. In ‘Jigsawed Greens’, excerpted exclusively below, his reminiscences on childhood obsessions seem to colour his every adult thought.

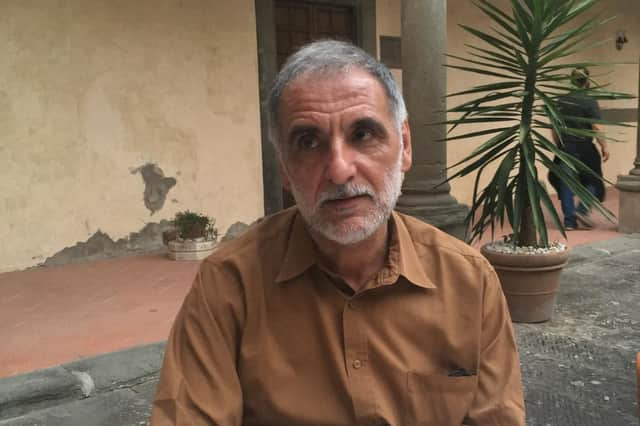

Mari has published ten novels, in addition to several short story and poetry collections in Italian and has translated classic novels by Herman Melville, George Orwell, John Steinbeck and H. G. Wells. He has received prestigious awards including the Bagutta Prize, the Mondello Prize and the Selezione Campiello Prize.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn a survey published by the magazine Orlando Esplorazioni in 2015, Mari was ranked the contemporary Italian author most likely to be read by generations to come.

The Sheffield Telegraph below publishes an exclusive excerpt from Mari’s You, Bleeding Childhood, translated by Brian Robert Moore, publishing 11 July 2023 by Sheffield press And Other Stories. It can be ordered from all Sheffield bookshops, including Rhyme and Reason (Hunters Bar) and La Biblioteka and Juno Books (both in the city centre).

[Extract]

JIGSAWED GREENS

The first puzzle depicted an Andean landscape by an anonymous Spanish painter from the nineteenth century, seven hundred and fifty pieces. My mother was the architect and the forewoman, I a stonecutter. My tasks were only menial: gather all of the sky-blue pieces into a corner, look in the box for a certain trefoil piece, reposition the cover displaying the image. With didactic zeal my mother provided commentary on her own work in order to reveal to me the method underlying it: not to rummage chaotically in the box, but scrupulously comb, flip, isolate; subdivide certain categories of pieces by hue or by grain, placing them in mugs, saucepans, saucers; gently lay the piece in its place without trying to force it; first compose the frame, then the easier figures, starting with their contours, and then, finally, the sky and the fields, starting with the horizon line; know when to stop insisting on resolving a given area in order to open a new front; remember that, as a general rule, a quatrefoil piece will tend to fall in a central square with sixteen pieces on each side; alternate a negative view with a positive view, dialectically tempering the search for fullness in known empty spaces with the emptiness of known full spaces; avoid relying on the initial compatibility of shapes, colors, and lines, but skeptically suppose, as a precautionary measure, a diabolical coincidence, and in the absence of absolute certainty, abstain.

A school of rigor, the rigorousness of that school . . . I had the privilege of placing a piece only toward the end of the next puzzle, a thousand-piece Hans Holbein: the fifth-to-last piece was granted to me, with a margin of uncertainty and responsibility that, while leaving intact the ease of this debut, did not in any way attenuate my nervousness. In order to put that piece in its place, I had needed to learn to hold it by the edges as one holds a photograph: lowering it, I had the sensation that it was melting into the painting like a drop of mercury. The correct insertion of that piece marked my initiation into the sublime discipline, the severe charm of which would reveal itself to me by degrees until the point where, as happens in the study of ancient Greek or algebra, proficiency strips itself of technique to become an animalistic source of pleasure. My mother, as is well known, was a virtuoso, a true jigsaw monster: in the span of two years, I acquired a sufficient amount of skill to keep her busy with competitions that, though still ultimately ending in her favor, were never completely free of uncertainty. By the start of the third year, I had reached her level. When three more years had passed, at the very moment when I brilliantly unraveled the arduous exegetic knot of a false shadow cone in a four-thousand-piece Altdorfer, she told me that I had become the best. Moved, I denied it; she hugged me, confiding that from my very first attempts she had been sure that it would happen, she had prophesied my glory upon crossing that last threshold, entering into that elysian rarefaction. Now that I’m alone and that threshold has long been crossed, I know that for a few seconds in her life she must indeed have had a fleeting vision of my destiny, so brightly did her eyes light up when she talked to me of that fantastical husk, the dissolution of technique, the absolute purification of the gesture, the physical, pre-mental knowledge of any given piece’s fate, its immediate positioning, not in the economy of full and empty, but in the nakedness of space, at the single correct intersection of virtual coordinates.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI am often visited and overwhelmed by the simultaneous memory of all the puzzles assembled before arriving where I am now: Cézanne, Pontormo, Corot, Zurbarán, Friedrich, Vermeer, Morandi, Klee, Pisanello, Van Gogh, Bruegel, Rembrandt, Goya, Van Dyck, these puzzles were also a way to learn art history in a non-scholastic fashion, through details and the physicality of the brushstrokes; in this, my mother showed the way unwaveringly, giving me to understand from the very beginning that any non-painterly subject would have had such a vulgar effect on our discipline as to deprive it of all sense. Out of a kind of discretion, in which pity and disgust were mixed as well, she never spoke to me explicitly of puzzles with photographic subjects, but I knew that her periphrases were alluding to those abominations, and the idea of such baseness disturbed me. Her intransigence immediately became my own: no less embarrassed, I still cannot lay my eyes on one of those boxes without feeling as scandalized as the Church Fathers before a heretic.