Book Club: Power, prejudices and uncomfortable truths exposed across the United States

McLean is the author of the acclaimed novel Pity the Beast, which is also out in paperback this month.

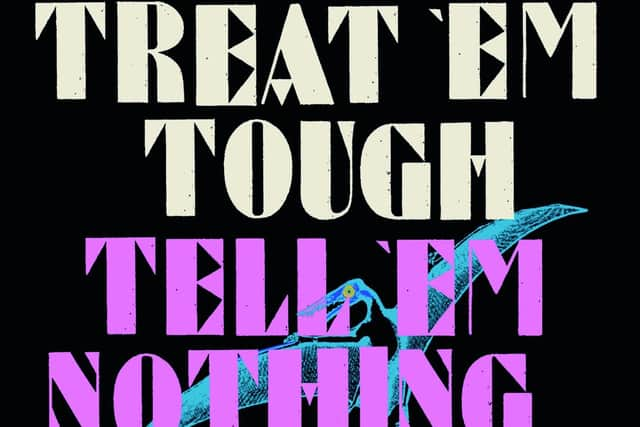

Dark, humane and very funny, these ten stories are the latest and best of Robin McLean’s reports from the eternal battlefront that is the United States.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEach finds a way into the nerves and blood where people's bodies and inner thoughts meet the world around us, whether that is human society or the forces of nature.

As The Guardian said when reviewing Get ‘em Young, Treat ‘em Tough, Tell ‘em Nothing: ‘McLean creates dense and memorable pictures of American life that are intensely and oddly real.

‘Underneath their fantasies of capacity and agency, McLean’s characters are, as the narrator in the superb House Full of Feasting says, “helpless, as we all are, every day of our lives”.

The following extract is taken from the short story ‘The Big Black Man’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDanny, a grad student from a wealthy area in Illinois, is desperate to prove himself an advocate for social justice.

However, as the narrative develops his own prejudices only become more and more apparent.

"I’m applying to graduate schools, he’d warned.

African American Studies.

Don’t be silly, she’d said.

For now, he was biding his time in printing, the front desk of the copy shop near the St. Louis Arch, where he made copies, reports with graphs, gladly, for people of every shade.

The boxy car returned head-on from the corner, seemed to hesitate as if looking Danny over, as if Danny was important to the occupant of the car for some reason.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut then it jumped, sped up Fern, turned left on Button Ball Street.

He told the dog to gitty up.

He wiped drops of damp from his face with his forearm.

He avoided cracks in the sidewalk.

More and more brick pillars stood under graceful iron streetlights casting umbrellas of light on edges of huge yards, marked out a century back by midwestern tycoons.

These men understood their own value, planted shade trees by seed for great-grandkids’ swings, built back entrances for servants, commissioned cast iron figurines for out front, with iron loops raised high for hitching teams of horses.

They were ambitious men who’d paid well for this breathing room.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the Hartleys’ house, Danny saw two black girls hiding behind a hedge.

Just girls, Danny rethought.

The dog was barking like crazy.

The girls glowed for a moment in the light of their cell phone through the newly trimmed leaves, a big girl and a slim one, then the phone went dark.

“OK, I see you there,” Danny said.

“Is that your yard?” He leaned for a better look in the shadow of the hedge.

“You think it’s my yard?” said the slim girl.

“You think we like sitting here on our behinds?

A car is tailing us. He’s been after us for blocks.

Our phone just died. You got a cell phone?”

Are you listening, Mother? That thesis won highest honors.

She’d smiled. I’m very proud of you of course.

He’d showed the thesis, a little tattered at the edges now, to a Mexican kid at the copy shop recently.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe kid said, What do you know about that stuff anyway? Danny had asked the kid to a Cardinals game.

Mother had sent him tickets. He went to the game alone.

The kid said he did not follow baseball.

“Are you undercover or something?” said the slim girl.

“Where’s your badge?”

A van passed, followed by a taxi, followed by a city truck with a logo on the side for the Sewer Authority.

The pipes and cisterns were overflowing from the storm.

In the headlights, Danny turned for a better look at the girls.

The bigger girl might have been pregnant, or just had baby fat in the midsection, a slight case of lack of control.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe slim girl looked stunted, twelve at first glance, but more shapely than the other girl, with a face more serious than sixteen, though poverty could age you.

They wore very tight jeans even in this summer humidity.

No sweat on their foreheads, thanks to eons in Africa, cruel climates in the American South.

He thought of the Mexican kid bent, filling a paper tray.

“I sympathize,” he said in the light of a motorcycle passing. “I’m on your side.”

“Thanks,” she said. “How did we ever survive without you.

"Got a phone? I can ring my mom up.”

Danny laughed. “Ring her up?”

“That means call,” the girl said.

“I know what it means,” he said.

An electric company cherry picker came and went.

“I live on this street,” he said.

“I grew up here. I’m just visiting now.”

“My mom’s employed on Western,” she said.

“She could arrive in the vicinity in five minutes flat.”

He said, “Vicinity? Just speak normally.”

“I read the dictionary each night before slumber,” she said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt this declaration the bigger girl laughed, as a bus lit them up through the hedge.

The slim girl poked the big girl in the gut, and they instantly entered into what he could see was a private joke.

They whispered back and forth.

Danny watched, excluded, leaned over the hedge to catch a word.