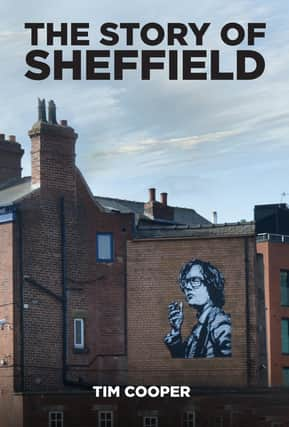

Book Club: Tim Cooper pays homage to Sheffield in this novel about the city through age

He has also published several books and articles on history and archaeology. Originally from Birmingham, Cooper has lived in Sheffield for more than 30 years.

As a Student Support Officer he regularly conducts local history walks around Sheffield for international students at the University of Sheffield, which prompted him to write The Story of Sheffield.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis epic new book charts the city’s long history of fierce independence and revolutionary spirit.

From Huntsman’s crucible steel in the eighteenth century, to Brearley’s stainless steel in the twentieth, Sheffield forged the very fabric of the modern world.

Cooper's narrative, which includes photographs of relevant locations throughout the city, graciously paints the unique character of Sheffield, its distinct communities, and its relationship to the natural landscape.

The Story of Sheffield is a timely reminder of what an incredible city Sheffield is and how it had to reinvent itself in the twenty-first century, forging a strong identity through its people and places.

The Sheffield Telegraph publishes here an excerpt from it.

The Human Cost [p.251]

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFrom 1979, Sheffield was shattered by redundancies on an unprecedented scale, two-thirds of which were in a steel industry reeling from the wholesale closure of production and engineering works. For the first time in its history, unemployment in Sheffield rose above the national average, peaking at just over 16 per cent of the workforce in 1987, amounting to some 50,000 people. In the tool sector, the number of workers fell from 20,000 in 1970 to 1,200 in 1991. In the South Yorkshire steel industry as a whole, the number of people employed fell from around 60,000 in 1971 to 16,000 in 1987, and below 10,000 by the early 1990s. From the mid-1980s, the social effects of mass unemployment in the traditional steel, engineering and cutlery sectors were to be devastating.

By any standards, the effects of the wholesale closure of steel and engineering works of the early 1980s were brutal. Coming on top of the slum clearances of the previous generation, many parts of the city’s East End were utterly devoid of either industry or housing. By 1988, fewer than 300 people lived in what had been Sheffield’s beating industrial heart and almost half of all land was either vacant or derelict. The great leviathans of Sheffield’s once-proud steel industry – Firth Brown’s, Hadfield’s and Brown Bayley’s – had all been completely flattened. About two-thirds of the registered unemployed were former steelworkers.

Given the nature of the job, these were men who had worked, as their fathers and grandfathers had done, in close-knit teams, each depending on the other. The sudden cutting of close ties like these, with their origins far back in Sheffield’s traditional cutlery industry, was to be catastrophic for generations to come. In addition to this human tragedy, in the space of just a few dramatic years, the whole Sheffield and Rotherham region was to lose its distinctive character as a centre for heavy industry that it had built up since the establishment of the East End works more than 100 years before. In the words of labour historian Sidney Pollard, ‘a significant chapter in the history of the city and the country, a distinguished chapter of success and achievement, had come to a close’.

In 1981 the council established an employment department to promote retraining for new skills and jobs, and began to devise policies to stimulate new investment in the city and investigate the creation of new employment opportunities. Already, by 1981, the male steelworker was no longer typical of Sheffield’s workforce, and in his place female workers in the service industries dominated the employment market, and the city’s main employers had become the council, the health authority and the institutions of higher and further education. Unemployment in Sheffield, which for decades had been lower than the national average, was now consistently higher. In parts of Sheffield, entire communities were out of work. Everywhere across the city there were families whose lives and futures were irredeemably changed, almost overnight. The choice facing those who governed the city in these dark times was stark. It was a choice of whether to accept the human cost of this tragedy or to fight back.