Sheffield Great Flood victims - the sad story of how children's lives were only worth what they would have earned

and live on Freeview channel 276

Churches and cemeteries including Wardsend Cemetery, Bradfield Church, Loxley Cemetery, Wadsley Church and Sheffield General Cemetery, are sharing stories about the lives of some of the victims and memorialising this tragic moment in Sheffield’s history.

The usual public commemoration of the flood which takes place on March 11 at the memorial to the victims on Millsands was not able to go ahead because of the pandemic, although flowers were still laid.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe General Cemetery has a round-up of sources of information online at https://www.gencem.org/thegreatsheffieldflood

Coun Mary Lea, cabinet member for culture, parks and leisure at Sheffield City Council, said: “The Great Sheffield Flood is one of the most significant events in our city’s history, that affected so many lives in so many ways.

"It’s important that we take the time to share and reflect on the experiences and stories of our citizens more than 150 years ago, and realise that although flooding still affects our communities today, we have come so far since then.”

Apologies to Mick for misspelling his surname last week. Here is his piece:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn continuing the A-Z of the Great Sheffield Flood victims buried in Loxley Cemetery, I must begin part two by going back to ‘B’ and the Bates family, as it was remiss of me not to mention Thomas and Harriet’s three sons, who also lost their lives that terrible night: 19-year-old George, 15-year-old Walter and Thomas junior aged 10 (according to burial records Thomas was 12). A fourth child, daughter Annie Bates, survived the Flood as she worked in service and was away.

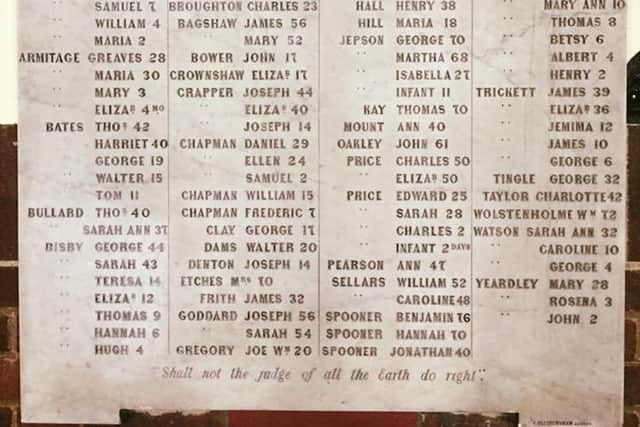

Young Walter was officially recorded as not identified but George and Thomas were buried with their parents at Loxley. According to the official list of the dead published by the Chief Constable, John Jackson, all four bodies were recovered at Green Lane. In respect of claims made against the Sheffield Waterworks Company, none was made for loss of life for any of the three sons but amounts were included in the claim for loss of property at the Bates household for their clothes: George, £7-15s; Walter, £6-15s; Thomas, £2 15s. Some of Annie’s clothes were also claimed for, amounting to £2-10s. It is sad to think that in 19th-century Sheffield, the poor children’s clothes were of more value than their lives.

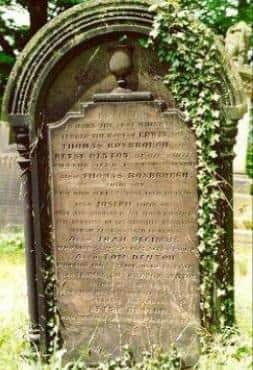

Our next victim buried in Loxley Cemetery is 14-year-old Joseph Denton of Old Wheel, Loxley. There is some confusion within the reports of Joseph’s demise as Samuel Harrison appears to have confused him with John Denton at the Chapmans’ cottage, who survived the Flood. However, there is no doubt that Joseph Denton was drowned, his body being found in the ruins of the Old Wheel on March 14.

His father, Thomas Roxbrough Denton, submitted a loss of life claim for his son and it is clear from the claim that the notional value of his son’s life was that which he was likely to earn over a period of six-and-a-half years, with deductions for his board. The amount claimed tells us that Joseph earned £1-10s per week, equating to £507. Out of this he paid 10 shillings per week board (£169 over six and a half years), leaving a net claim of £338.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI would like to have been a fly on the wall when the Commissioners discussed this claim to see how they determined that Joseph Denton was actually only worth £153-3s. Burial records at Loxley Church indicate that one Thomas Denton, who also died in the Flood, is also buried there but he cannot be found in any of the lists of the dead. This remains a mystery for members of the Friends of Loxley Cemetery Group to try and unravel.

For our next Flood victims buried at Loxley we return to Malin Bridge, the Grim Reaper’s favourite haunt that dreadful night. In one of three cottages that stood near the confluence of the rivers Loxley and Rivelin at Malin Bridge lived the Hudson family.

Forgeman, 39-year-old John Hudson and his wife Eliza, also 39, were probably asleep in bed when the cottages were swept away by the spreading wall of water that swept through the village. Their two children, eight-year-old Mary and four-year-old George, were taken with them. The bodies of young George and John were found in Sheffield on March 12 and 14 respectively. The location of Eliza’s body was not recorded but was found nevertheless.

However, there was some initial confusion about Mary, who was recorded as not identified in the official list of the dead, which also indicated that John, Eliza and George were buried at Loxley, suggesting that Mary hadn’t been found at the time of the burial. Mary’s body was later found and identified, then buried with her family, her name being added to the bottom of the gravestone.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe confusion was further fuelled by the two claims made for loss of life. In the first claim, which was in respect of John, Eliza and two children for £200, the beneficiaries are named as Robert Gregory, George Hudson and William Hudson, who actually submitted the claim. Due to the legal definition in respect of beneficiaries, they must be a parent, spouse or child of the deceased.

George Hudson is likely to be John’s father as Karen Lightowler’s research found that John’s father was named George. However, William Hudson and Robert Gregory could not be beneficiaries. This is probably why the claim was dismissed.

The three men, acting as administrators, also submitted a claim for the Hudsons’ property lost in the Flood and for funeral expenses. The property consisted mainly of clothes, furniture and other household items. The only personal item listed was a gold watch and chain belonging to Eliza valued at £10-10s. The claim totalled £147-6s-6d, of which the Commissioners awarded £60.

The second loss of life claim was in respect of John and Eliza Hudson and their ‘daughter’; little George was not included in the claim – being just four years old he would be no source of income for the family and therefore of no material value.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe confusion arises from the claim being made by Annie Burgin (spinster) and Rebecca Burgin (widow) of Loxley Bottom, acting as ‘guardian and next friend’ of the beneficiary, who was an unnamed child, ie a child of John and Eliza Hudson. The claim was for £500 and was withdrawn but who was the child?

Karen Lightowler unearthed the solution to this mystery as she found that Eliza (nee Burgin) had a daughter before she married John Hudson and named her Ann, hence Annie Burgin, spinster, who submitted the claim with her grandmother, Rebecca Burgin. Annie Burgin was the beneficiary of the claim but she received nothing.

Until pretty recently it was thought that the body of Selina Turner was buried at Wadsley Church. However, research undertaken by Malcolm Nunn and the late John Bailey discovered that she was actually buried in a Loxley grave. Selina was the 39-year-old wife of 48 year-old saw grinder Isaac Turner and they had two children, Sarah Ann, aged 10, and Isaac junior, aged eight. The family lived at Hillsborough near the end of Holme Lane.

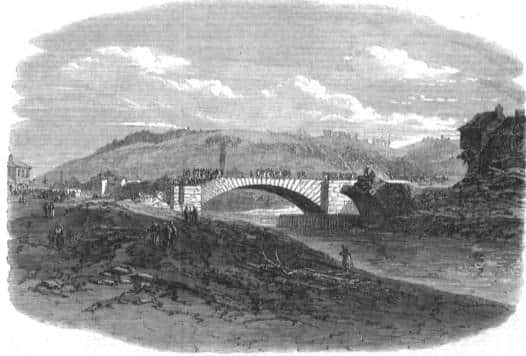

Living with the Turners and being nursed at the time was Herbert Gravenor Marshall, the two-year-old son of Sheffield pawnbroker William Wright Marshall. The infant perished along with the Turner family as the Flood destroyed most of the buildings in this vicinity, along with Hill Bridge, much of which helped save Hillsborough Bridge as debris from its collapse acted as a buffer to protect the span of the second bridge, which only suffered damage to its walls and parapets as the water smashed over it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe body of Sarah Ann was not identified but the two Isaacs and Selina were recorded in the official list of the dead as having been buried at Wadsley Church but Karen Lightowler’s research found that only Isaac and their son were buried at Wadsley.

The whereabouts of Selina became a mystery until Malcolm and John discovered she was buried in a plot in Loxley Cemetery owned by one George Wilde, a friend of the Turner family, on May 6, 1864. The burial record states ‘By flood, Hillsborough’. Clearly Selina’s body wasn’t recovered on March 14, as recorded in the official list, but much later. Decomposition of the body would have necessitated a hasty burial and the plot at Loxley was perhaps the easiest option at the time.

We have come to the end of the A-Z of victims buried at Loxley from the official list of the dead but there were subsequently other poor souls who later died from conditions that they developed as a result of their trauma that night.

Shoemaker Jeremiah Buckley lived at 1 Brick Row, Holme Lane, with his nine children and his sister, a widow named Hannah Birks. Although Jeremiah survived the night of the Flood he developed a fever from his ordeal, from which he never recovered and he died of pneumonia on August 12, 1864.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe didn’t live to see the outcome of a claim he and his fellow shoemaker, George Burrell, had submitted for their losses on the night: 48 pairs of ‘men’s strong lace boots ready for bottoming’ valued at £12. They were awarded £9-6s in July 1865. Hannah Birks submitted a loss of life claim on behalf of the children for £1,000; they received £229.

Jeremiah’s wife, Mary, had passed away two years previously and was buried at Loxley Cemetery, where she was now joined by her husband. My research for this article has highlighted an error in my book, Inundation, in that I suggested that Jeremiah Buckley may be the father of the child Mrs Birks was confined with that night.

This was probably not Hannah Birks that Samuel Harrison had referred to as Jeremiah Buckley and Hannah were siblings, something I have only now uncovered. In the words of Oscar Wilde ‘The only duty we owe to history is to rewrite it’. I will be rewriting this bit should a second edition be published.

Our final family of Flood victims buried at Loxley Cemetery is the Proctor family. Unlike the others, where there is clear evidence of their death being directly linked to the Flood, the connection that their deaths had is pure conjecture but convincing nevertheless and I’m grateful to Karen Lightowler for her detective work.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere were four members of the Proctor family who Karen is convinced died indirectly as a consequence of the Flood: 49-year-old Mary (died May 30, 1864), 31-year-old George (died August 18, 1864), 26-year-old Alfred (died May 6, 1864) and Edwin, aged just 8 months (died July 23, 1864), all living in different households in the Hill Bridge and Owlerton areas. It was the dates of their deaths that drew Karen’s attention to them.

All of the same family, their relationship is a little complicated and takes some digesting. Mary’s husband, William, was Alfred’s brother and George’s cousin. The infant Edwin was George’s nephew. William was also the brother of the above Jeremiah Buckley’s wife, Mary. We needn’t delve any further but anyone wishing to view the whole family tree can find it in Karen’s book on the Aftermath.

The cause of death attributed on their death certificates also gives grounds to the Flood connection. Mary, who lived at High House Terrace, off Penistone Road (then Low Road) and behind Capel Street (then Chapel Street), died from ‘paralysis of one and a half years and dropsy, six months’. Whilst the paralysis, due to what we do not know, would not be made worse by the Flood, it may have hindered her escape from her ordeal.

Dropsy (oedema), on the other hand, is an excess of watery fluid in the cavities or tissues of the body; something that could be exacerbated by immersion in filthy water.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGeorge, who lived at Owlerton, died of hepatitis, a viral infection of the liver, which too could have been caught from toxins in the water. Alfred’s death was due to ‘Chronic Phthisis 7 years’, otherwise known as pulmonary tuberculosis. Although a sufferer for seven years, being caught up in the Flood would have accelerated his looming demise.

The infant Edwin died of bronchitis at Hill Bridge. Of such a tender age, he was vulnerable to any disease that emanated from the filthy waters but, as with each of the Proctors, linking it directly to the Flood is pure conjecture. The four Proctors were interred in separate graves at Loxley with Mary joining her husband William in his.

There ends the story of the Sheffield Flood victims buried at Loxley – for now! I have no doubts that the Friends of Loxley Cemetery Group will unearth (pardon the pun) more indirect links in the future.

Mick Drewry’s book Inundation is available direct from the author – email [email protected]. To contact Friends of Loxley Cemetery, email [email protected].