VE Day letter from the king but no chocolate for Sheffield schoolboy Peter

and live on Freeview channel 276

Peter Hemmingham, who now lives a busy life in Scarborough, was a pupil at Firth Park Grammar School.

He recalls: “I was aged 12. On the day itself we were at school when it was announced. We had the assembly where we were told and then we all went home.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Then, of course, all the celebrations had to be arranged. I lived in Bankfield Road, Malin Bridge. We had a street party.

“Rationing was on and the usual foods weren’t always available. All the women had to go out and bake and make all the arrangements and get the tables and everything else.

“They had a military parade in Weston Park on the Sunday and the mayor organised a ball in the town hall. That all took place afterwards.

“Sheffield was still suffering from the Blitz. There was no rebuilding at the time.”

Peter remembers the bombed-out city centre and other areas.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdChurch bells also rang out, the first time they had been heard for years.

There was one disappointment for Firth Park pupils, he says.

“Across the road to the school we had quite a big playing field and the underground shelters were there,” he says.

“In the shelters there were boxes and we didn’t know what was in them until the war had finished. We were told they were filled with chocolate bars – ‘in case’.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, the shelters were not used because all the Sheffield air raids were at night, says Peter.

“It was announced at the school that all the chocolate bars were going to come out. They were going to be distributed to the schoolkids.

“The following day there was another announcement: ‘You’re not going to get the chocolate. It’s going to the local orphanage’.”

Peter says the rare treat had been highly anticipated, although he wondered what state the chocolate might have been in after years underground.

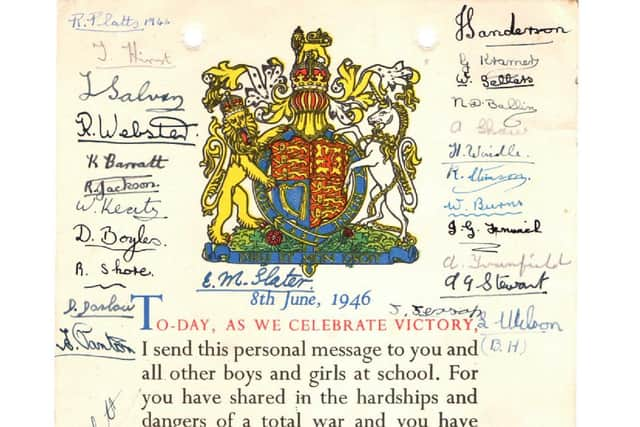

The souvenir he did receive is pictured here.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is a letter from King George VI, thanking schoolchildren for their role in the war effort. Peter’s is signed by his classmates.

Peter recalls the street party: “The kids got together and had games. Most of the adults were reminiscing and talking and we lived near St Polycarp’s Church with a lot of allotments close to it.

“My friend Stan Jolly’s father had an allotment on there and we used to go and play on there. We went with the girls as well.

“A certain amount of frivolity and kissing went on.”

He remembers a general feeling of relief that War was coming to an end, although ‘as kids, quite frankly, it was a bit of an adventure in a way’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We had to make our own amusement and we went to a wood yard to pick up cut-offs and started to make toys out of it. We had to be self-sufficient.”

Peter points out that he was born in 1933, the year Hitler came to power, so that dominated his entire childhood.

He remembers walking on a beach in Swansea on a family visit when the announcement of the War came and the family rushing home – then nothing happened for six months.

His father had served in the First World War, but was too old to be recalled to duty, so he acted as a firewatcher, spending nights on the roofs of buildings directing fire teams to where incendiary bombs had landed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWalter Hudson, Peter’s uncle, was serving in the Navy on board HMS Fearless when it was torpedoed and sunk and he was reported missing.

Peter’s grandmother received a telegram with the worrying news.

Walter was rescued and was put ashore in South Africa, where he served in the navy there for the rest of the War.

Peter remembers spending the nights of the Blitz sheltering under a table in the family’s cellar kitchen.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen he left Firth Park School at 16 in 1949, Peter was taken on as only the second cadet with the Sheffield City Police force. He worked in the warrants and prosecution office, checking that all the court paperwork was correct.

Later, after National Service in the RAF, he took legal exams and was seconded to help in the amalgamation of Greater Manchester Police from smaller forces and later moved on to work in the Home Office.

His son, John, is a well-known figure as the leader of the England band, a role that takes him all over the world watching the England football team.

Peter says that began because John took a trumpet to Sheffield Wednesday matches to lead singing to counteract negative chanting in the crowd.

That led on to forming the famed Sheffield Wednesday band and now the England one.

His proud dad is disappointed at just one thing, though – Peter is a lifelong Blade..